What is Natural History?

Feature image: Stromatolites from Shark Bay in Western Australia. Source

Natural history is the study of “nature’s story” – how our world became the way it is and what it means for our present and for our future.

Much as historians consult physical and written evidence to reconstruct human history, scientists who study natural history, called naturalists, consult similar evidence to reconstruct the history of our planet.

Natural History’s Christian Roots

Although dominated by secularism today, the study of natural history, in its modern sense, began with the work of Christian scholars during the 17th Century.

While chronologists like James Ussher were busy cataloging human history, others were taking the first steps towards a proper study of nature’s history.

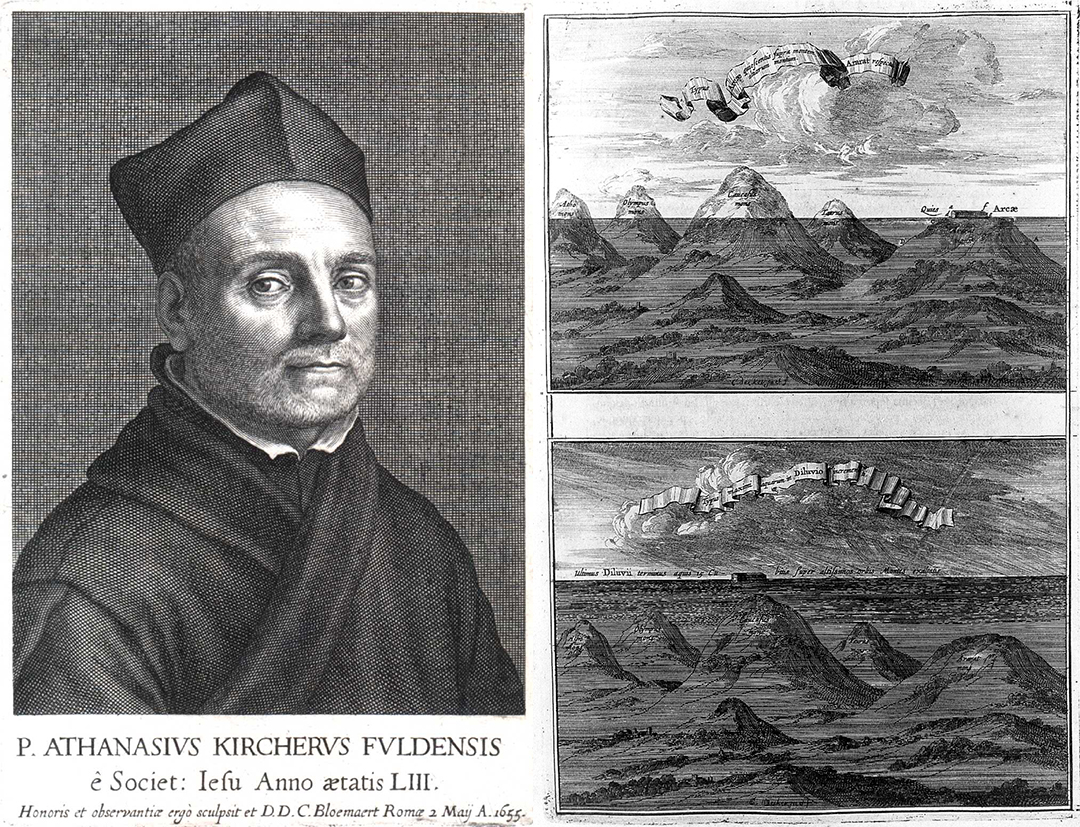

In 1675, Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher published a volume called Arca Noë (Noah’s Ark).

Left: Athanasius Kircher, pictured in his book Mundus Subterraneus. Right: Engraving from Arca Noë, showing the Ark coming to rest on Mt. Ararat. Source

In it, Kircher analyzed the account of Noah’s flood historically, developing models for the ark’s construction, its possible layout, as well as early explanations for the flood’s cause and descriptions of the Earth’s recovery afterward.1)Rudwick, M. J. S. “Making History a Science.” In Earth’s Deep History: How It Was Discovered and Why It Matters, 23. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014.

Kircher’s map of the world after the flood. Shaded areas represent hypothetical submerged pre-flood land masses. Source

Being similar in spirit (if archaic in form), Kircher’s work anticipated that of biblical naturalists in the centuries to come.

The Christian worldview was critical for the development of natural history. Unlike the philosophies of other cultures, Christianity gave its followers a sense that the world actually had a history to study.

Historian Martin Rudwick explains:

Most pre-modern societies around the world embodied in their cultures an assumption that time – or rather, the history that unfolds in time – is repetitive or in some sense cyclic, not arrow-like or uniquely and irreversibly directional . . . Against this background, the idea that the world has had a unique starting point and a linear and irreversibly directional history – an idea that first emerged in Judaism and was extended in Christianity (and later in Islam too) – stands out as a striking anomaly.2)Rudwick, M. J. S. “Making History a Science.” In Earth’s Deep History: How It Was Discovered and Why It Matters, 28-29. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014.

Studying Natural History

Biblical naturalists like Kircher employ a combination of textual evidence and physical observation to understand the past – interpreting the natural world through the lens of recorded history.

This is quite similar to how historians study human history, and for good reason.

Consider the fields of science and history for a moment. Though both ask questions about our world and often compliment each other, they have key differences as well.

[feature_box style=”10″ only_advanced=”There%20are%20no%20title%20options%20for%20the%20choosen%20style” alignment=”center”]

Science is a field of general inquiry about how the world typically works. Based on the principle of repeatable observation, it asks general questions and seeks formulaic answers.

[/feature_box]

[feature_box style=”10″ only_advanced=”There%20are%20no%20title%20options%20for%20the%20choosen%20style” alignment=”center”]

History is a field of specific inquiry about particular events. Unlike science, subjects of history are singular events in time – by definition unrepeatable and often unobserved by the historian.

[/feature_box]

Natural history is primarily a study of the past, and, therefore, a study of history. Its subjects (e.g. the origin of life) are singular events that are generally unrepeatable and typically unobserved by the naturalist.

Because of this, naturalists must “borrow” observations – consulting textual evidence to establish context and meaning, while examining physical evidence to fill in details and settle controversies.

History and Prehistory

Many naturalists try to bypass the use of textual evidence, claiming that much of natural history is so old that no human records exist from these periods.

This belief is tied to the idea of prehistory, which proposes that human beings are but insignificant latecomers to the long drama of life on Earth.

Most people are familiar with this concept, but is it true?

To properly evaluate the idea, one must know where it came from. During the first half of the 17th Century, the study of natural history was dominated by a largely biblical understanding of the past. This cast human beings as appearing early on in Earth history and playing a pivotal role in its unfolding story.

As the 17th Century gave way to the 18th, new developments in the fields of paleontology and geology seemed to challenge the conventional wisdom – in particular, the simplistic notion of Noah’s flood (an important biblical and geological event) as being a simple, forty-day-long surge of water.3)Rudwick, M. J. S. “Expanding Time and History.” In Earth’s Deep History: How It Was Discovered and Why It Matters, 81-82. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014.

Thin laminations, as seen in this block of travertine, are thought to form only in tranquil water and were one of the discoveries that shook early naturalists’ faith in the Bible’s history. This concern was misplaced, however, as Noah’s flood could easily produce these features during local periods of calm. Source

In reality, the Bible describes the flood as a complex, year-long event, more than capable of explaining the evidence presented, but the negative publicity had done its damage and many naturalists began to drift from biblical history.

Disillusioned with the traditional ideas, and spurred along by new, flawed readings of the book of Genesis, naturalists began conceiving Earth history as a mainly pre-historical narrative, with human beings only appearing near the end of a very long natural drama.

There was no real proof of this, of course, but the idea fueled the imaginations of naturalists for the next hundred years or so, resulting in a gradual secularization of the field.

Today, the concept of prehistory is taken for granted by most – which is unfortunate, given its shaky origins. Though understandable at the time, further research has shown that most all of the evidence that disturbed these early naturalists can be easily explained when one combines scientific knowledge with a proper understanding of the biblical text – a combination of physical and textual evidence!

Again, while physical evidence can be a plentiful source of information by itself, the importance of using both physical and textual evidence when studying history cannot be stressed enough.

Biblical geologist John Reed explains:

Archaeologists can discern the forensic evidence of Rome burning in AD 64, but can never address the likelihood of Nero’s involvement or his motivations. Only careful study of the testimonial evidence can supply the outline of the story. Heinrich Schliemann (1822–1890) found Troy not because he was led to it by artifacts, but because he followed the evidence found in Homer’s written testimony.

What does all that mean? Simply put, the 18th century flight from biblical testimony guaranteed a weak natural history by trying to enforce scientific certainty in an area inherently less knowable.4)Reed, John K. “Cuvier’s Analogy and Its Consequences: Forensics vs Testimony as Historical Evidence.” Journal of Creation 23, no. 3 (December 2008): 115-20.

Finding Nature’s Story

So what happens when we interpret nature through the lens of biblical history?

That is a question that biblical naturalists have been studying for hundreds of years. During that time, they have developed models to help us understand what we see in the nature.

These models are not perfect. They are changed or replaced as new information becomes available, but such is the way of science- even historical science.

At Orchard of Life Science™, we do our best to bring these models to life, combining the latest research with cutting-edge artistry to inspire others to pursue the fascinating subject of biblical natural history. We encourage you to visit our Interactive Timeline, for an immersive “walk through time,” based on current thinking from biblical naturalists around the world.

References

| ↑1 | Rudwick, M. J. S. “Making History a Science.” In Earth’s Deep History: How It Was Discovered and Why It Matters, 23. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Rudwick, M. J. S. “Making History a Science.” In Earth’s Deep History: How It Was Discovered and Why It Matters, 28-29. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014. |

| ↑3 | Rudwick, M. J. S. “Expanding Time and History.” In Earth’s Deep History: How It Was Discovered and Why It Matters, 81-82. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014. |

| ↑4 | Reed, John K. “Cuvier’s Analogy and Its Consequences: Forensics vs Testimony as Historical Evidence.” Journal of Creation 23, no. 3 (December 2008): 115-20. |

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.